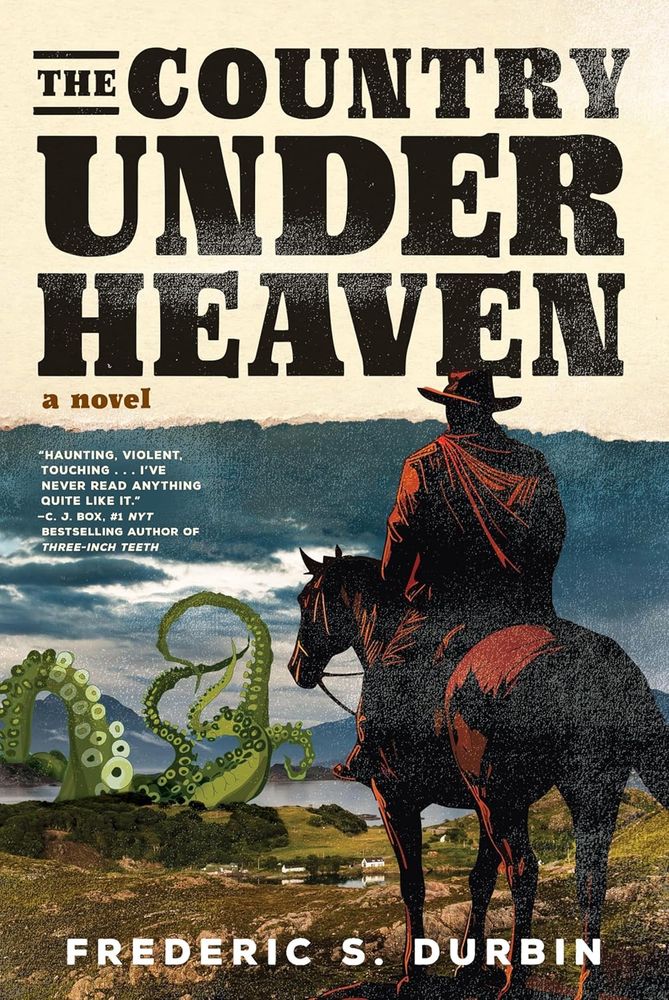

Until this past December, I was working at an independent bookstore, and one of the greatest perks of working at an independent bookstore is ARCs: Advance Reader’s Copies, books sent to stores and reviewers some months prior to the publishing date–usually sans some design flairs and the last bit of editing–so that informed reviews are already out in the world by the time the book hits the streets. The last such ARC that I grabbed from my old job was for a book called The Country Under Heaven by Frederic S. Durbin, the cover of which immediately captured me: a stark blend of photography and illustration, depicting a mounted cowboy in stark chiaroscuro looking out over a serene prairie landscape from whence a colossal betentacled horror is emerging in the distance. Nonetheless, that enticing cover might have sat unread on my shelf until long after the book came out, had it not also caught the attention of Bluesky user Kurt Busiek about a month ago. As you might see in that thread, he encouraged me to report back on it, and being a sucker for the flimsiest encouragement to be productive, I decided to jump on it for my next read and return to my neglected Book Reviews.

The Country Under Heaven follows Ovid Vesper, a Union Civil War veteran who, ever since almost getting blown up at Antietam, has been plagued by strange visions that grant him a keen, almost prescient awareness of the supernatural phenomena he encounters as he wanders the American frontier over the course of the 1880s with his trusty horse Jack (short for Flapjack). The book is structured as a series of horror or fantasy episodes, each chapter being its own short story or novelette length tale (the first and second-to-last were previously published in anthologies) demarcated by the year and state, in which Ovid relates in a stern first person encountering or confronting some mystical event. Throughout the book, Ovid runs into psychic children, Lovecraftian horrors, and outsized yokai–there’s generally no overarching worlbuilding all of these are all descended from, rather it evokes a Kitchen Sink, where absolutely anything might be found among the vastness of the West, the only real consistency being a shadowy thing Ovid calls the Craither, which has stalked him since Antietam.

Really, the impression is of nothing so much as a selection of fan-favorite episodes of some late-nineties/early-aughts Monster-of-the-Week series; a Spaghetti-Western companion to the likes of Buffy, The X-Files, or Xena, which as I type this I’m surprised didn’t actually exist with the same pop cultural cachet. Every story works individually, and there’s just enough connective tissue between them to keep the broader narrative from feeling aimless. While often falling within the broad umbrella of “Horror,” the stories are never overly graphic or frightening–in fact there’s a strong sense of wonder at nature, and purpose throughout which I would argue stands somewhat at odds with the Lovecraftian ethos implied by the cover art.

As for Ovid himself, he’s a bit plain as far as protagonists go, but that’s suitable to the roll he fills. A man of seemingly bottomless sympathy, who prides himself on knowing the names and seasons of the flowers that dot the prairies and the deserts. He’s an everyman that exists within the story to move through it with wisdom, kindness, and when necessary a well-aimed gun.

If I have one major critique of The Country Under Heaven, it’s that, for my own taste, it was a bit toothless for its own milieu. The first chapter seems to set the stage for a grounded exploration of the harsh realities of life on the frontier: children killed or crippled by plague and violence, con-men preying on the insecurities of the struggling masses, and true justice hard-won where it can be found at all. And the horror genre suits that conceit sublimely–the fundamental strength of speculative fiction is that it allows the author to present the conditions of the real world in the sharpest possible contrast. But much of the middle of the book is set rather firmly within the romanticized idiom of the Western: white-hatted law men and deputies up against black-hatted bandits in gunfights for control of an idyllic west, perturbed almost exclusively by the supernatural. Ovid pays frequent lip-service to his contempt for the “Reb”‘s slaveholding and to the plight of Indigenous Americans, but the book seems disinclined to grapple with the roll the American Frontiersman–which the Western as a genre lionizes–played in those injustices. Hardly new for the genre, but Ovid’s commentary gives some impression of trying to have your cake and eat it too; the characters gleefully participate in the resettlement of the Capital-W West, but our noble protagonist shakes his head ruefully whenever its original inhabitants come up to let us know he feels ashamed about it.

My bleeding heart aside, The Country Under Heaven is a solid read. Well paced, with a coherent vision, it’s a good choice for fans of Westerns or of light, evocative horror or fantasy, or just someone looking for bite-sized stories. It’s due out on May 13, you can find the publisher here, but I would encourage you to seek it out at your local independent bookstore. Maybe someone there has also read it ahead of time, and can tell you more about it.